The (False) History of Ninja Action

Our latest OOP booklet essay is an introduction to the Shinobi series

Radiance is looking to keep the great writing in our booklets available over time with a long-form online presence. So we’ve started a Substack to host otherwise out-of-print essays alongside personalised recommendations. Thanks for joining us as we settle down for some special features.

RADIANCE RECOMMENDS: NINJA FILMS

Tom: Ninja in the Dragon’s Den (1982). It's Shogun's Hiroyuki Sanada vs Hong Kong martial arts legend Conan Lee, both in the prime of their youth as a ninja from Japan and a smug kung fu prodigy who form an uneasy transnational alliance. This was the debut film by one of HK's finest action directors, Corey Yuen.

Paul: One of the defining features of the real-life ninjas that have inspired so much pop culture over the years is their background: often, the ninja were peasants, hailing from the very lowest strata of Japanese society, and therefore standing in stark contrast to the samurai, who often came from nobility and represented honour and the upholding of fine tradition. The ninjas meanwhile were defined by their scrappiness, lawlessness, and willingness to use any underhand trick to achieve their aims; so with that in mind it’s perhaps appropriate that while the samurai movie will forever be inextricably linked with great masters of Japanese cinema such as Kurosawa, Michoguchi, Kobayashi, for me, the ninja are predominantly associated with disreputable, violent, extremely entertaining shlock. In other words - with the notable exception of the Shinobi on mono series - there are samurai films, and ninja movies.

Two of my favourite ninja movies feature bands of ninjas uniting to take on lone-wolf samurai in the role of formidable antagonists. In Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to the River Styx (Kenji Musumi, 1972) - arguably the strongest film the Lone Wolf and Cub series and the primary source of footage for the grindhouse English language re-edit Shogun Assassin - a clan of sadistic female ninjas provide Tomisaburo Wakayama and son with one of their most memorable opponents, with a remarkable introductory scene where they reduce a male ninja to a Monty Python-esque limbless torso in a matter of seconds. And Duel to the Death (Ching Siu-tung, 1983) arguably provides the most bang for your ninja buck, with a feature-length onslaught of ninjas of different shapes, sizes and identities, with a calvacade of exploding kamikaze ninjas probably being the highlight.

This emphasis on mad stylish violence, rather than being burdened with the cumbersome responsibility of exploring complex ideas of Japanese cultural identity and institutional loyalty, allowed the West to get it on the act with several notable ninja movies of their own. Obviously, you can’t talk about low-budget shlock without mentioning Cannon Films, who made an entire ninjasploitation cottage industry in the 80s in their many collaborations with former All Japan Karate champion Sho Kasugi. My favourite is the frankly deranged Ninja III: The Domination (Sam Firstenberg, 1984), an all time great work of trash which sees the Cannon machine blend the ninja mythos with possession horror, Flashdance, and an aerobics instructional video, to dizzying and hysterical effect.

Then more recently, the ninja proved a reliable source of material for the early 2010s DTV action revival, providing Scott Atkins and Isaac Florentine with two of their best vehicles in Ninja (2009) and (particularly) Ninja 2: Shadow of a Tear (2013).

Finally, I’d be lying if I said that there wasn’t a special place in my heart for the film and series that introduced me and anyone else old enough to remember the UK nun-chuck moral panic to the ninja mythos in the first place: the original Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles (Steven Barron, 1990), a bizarre and remarkable comic adaptation that somehow applies the inch-thick-layer-of-grime NY aesthetic of films by Abel Ferrara and Frank Henenlotter to…a kids movie? And it works? Add in some Jim Henson Creature Workshop puppetry and practical effects that remain impressive to this day and you have a delightful, none-more-90s oddity – the long rumoured 4K release can’t come soon enough…

OUT-OF-PRINT ESSAY: “BAND OF ASSASSINS“ BY JONATHAN CLEMENTS

Like Rasputin the indestructible monk, the samurai warlord Oda Nobunaga (Tomisaburo Wakayama) proves to be a difficult foe to kill. But that doesn’t stop a clan of ninja from doing the best they can, dripping poison into his mouth while he sleeps, and enacting arcane sorcerous rituals to push him over the edge into death. But who is to say such things did not really happen? How many strange falls and sudden illnesses of the samurai era might have been the work of cunning assassins, lurking beneath the floorboards and in the attic?

Such is the rhetoric of ninja stories since their first flourishing in the 1950s. The absence of proof is itself taken as some form of facetious evidence: a massive cover-up to erase the true heroes from Japanese history.

Shinobi no Mono does not shirk from the idea of ninja as apolitical mercenaries, but its first act establishes that even they have principles. Momochi Sandayu (Yunosuke Ito) the village elder explains to his people that the warlord Nobunaga has to be stopped. He also spins an entirely fictional genealogy of ninjutsu that claims it was founded in the dark ages and was a secret skill of the Buddhist fighting monks that Nobunaga has wiped out on Mount Hiei. It is a typical case of ninjutsu fake news, citing a historical incident, shoving ninja into it, and shrugging if no-one was left alive to confirm the claim. Shinobi no Mono demands that the viewer accept its central conceit – as if a newly made Robin Hood movie wanted everyone to agree he was also a vampire.

Even its title is a subtle gesture of feigned historical accuracy. The term ninja is a creation of the twentieth century, but its component parts, read as “shinobi [no] mono,” can be found in multiple historical accounts. Literally meaning “people of stealth”, it referred to scouts, sappers and spies, but has been retconned by modern authors who wish to imply that all such appearances were manifestations of a secret cult of magical assassins.

One such author was Tomoyoshi Murayama (1901-77), a darling of the Japanese Left, once hounded out of the country, but now thriving in Japan’s post-war society. Returning to Japan in 1923 after studies in Germany, Murayama had been a key figure in Tokyo’s agit-prop theatre, participating in Marxist re-readings of Robin Hood and Don Quixote, and working as a book illustrator with the pen-name “Tom.” His career as a playwright began in earnest with Nero in a Skirt (1927, Skirt o Haita Nero), a satire on the life of the Russian ruler Catherine the Great. He attracted unwelcome attention from the Japanese authorities with another play, Record of a Gang of Thugs (1929, Borokodan-ki), which lionised Communist agitators and strikers in a real-life Chinese railway incident two years earlier.

Such activities ran contrary to Japan’s 1925 Peace Preservation Laws, a parcel of legislation that criminalised any threat to the Japanese “national spirit” (kokutai). In advocating for the dissolution of the monarchy, socialism and Communism were hence treasonous, and with the inauguration of a “Thought Section” of the police in 1927, Murayama soon became one of the prime targets for harassment.

He was arrested in 1930 and 1931, officially recanted his Communist views, and spent much of the years of Japan’s long war flirting with controversy in the form of “updated” kabuki plays. Arrested again in 1940 and under probation thereafter, he jumped bail and ran for Korea and then Manchukuo, parts of the Japanese Empire where he could lose himself in the crowds and chaos.

Returning to Japan in 1945, Murayama enjoyed a brief renaissance of his theatrical career, capitalising on the Occupation regime’s encouragement, for a time at least, of any figures who had been ideologically opposed to the defeated militarist government. As attitudes began to freeze into the early days of the Cold War, Murayama’s theatrical troupe was a conspicuous supporter of the People’s Republic of China, embarking on three tours behind the Bamboo Curtain.

He is, however, best remembered for the book sequence Shinobi no Mono, the first volume of which ran from November 1960 to May 1962 in Akahata (“Red Flag”), the newspaper of the Japanese Communist Party. Murayama’s historical fiction reimagined the wars of Japan’s samurai era not from the top-down perspective of samurai warlords, but a worm’s-eye view from the very bottom of the social order, among the peasant assassins variously persecuted, oppressed and occasionally appropriated to do the dirty work of their samurai masters. His work occupied a similar position in Cold War fiction to that of the manga artist Sanpei Shirato and the novelist Futaro Yamada, whose respective Ninja Handbook of Martial Arts (1957, Ninja Bugei-cho) and Koga Ninja Scrolls (1959, Koga Ninpo-cho) had also introduced an imaginary underclass perspective on the military history that had been such a mainstay of the discredited wartime regime.

For such Cold War creators, all the old tales were dismissed as propaganda. The people had been lied to by their masters in the 1930s and 1940s, and finally the real story (as they imagined it) could be told. In Murayama’s case, he focussed on Goemon Ishikawa (Raizo Ichikawa), a folk hero who had been legendarily boiled alive after a failed assassination attempt on the warlord Hideyoshi, that same “Monkey” (Matasaburo Niwa) who would rise to power after Nobunaga’s death. Much of preceding folklore about Ishikawa had favoured his Robin Hood-like reputation as a man who robbed from the rich and gave to the poor. Here we see him in his younger days, as a callow youth framed and cast out thanks to the petty rivalries of another clan and his own inadvisable dalliance with his boss’s neglected wife Ino-ne (Kyoko Kishida). The ninja of Shinobi no Mono are turning on each other, as the supposed Communist allies, the Russians and Chinese, threatened to do in the 1960s, the higher purpose of the ninja manipulated by the warlords or defeated by self-interest.

Goemon is offered an unusual temptation. He brags to his father (Koichi Mizuhara) that he’s getting a fantastic promotion, away from active duty to become the villager elder’s chief accountant. His father sternly admonishes him about his attitude. As a ninja, he should be volunteering for a life of noble struggle, of duties assigned to him in great danger, and the ever-present risk of capture, torture and death. If such a lecture recalls Party political propaganda from the Soviet Union or the People’s Republic of China, it is no coincidence. The ninja of Satsuo Yamamoto’s Band of Assassins are almost as opposed to bourgeois life as they are to predatory warlords. The bad-guys in the film do not solely comprise the evil samurai, but also the enemies of the people, such as Kizaru (Ko Nishimura), a fellow ninja who is resentful of Goemon’s prowess and success.

In the leading role of Goemon, Raizo Ichikawa VIII has a face that invites envy. Ichikawa was himself something of an outlaw figure, a young kabuki protégé who, it was alleged, had turned his back on the theatre over his frustration with minor roles. Proclaiming cinema to be a medium for youth, and pointedly threatening to return to kabuki when he was an old man, Ichikawa became one of Japanese media’s first post-Occupation heart-throbs, adding gravity to several 1950s movies. After his star turn as a troubled monk in Kon Ichikawa’s Conflagration (1958, Enjo), the actor’s rise to fame was sealed, and it helped that in 1962, the year of the release of the first Shinobi no Mono film, he married the adopted daughter of the Daiei Films studio head, Masaichi Nagata.

Shinobi no Mono displays the hallmarks of a script struggling to accommodate the peculiar background of its star. Ichikawa was not a martial artist, and was famously frail. Consequently, his first-act fight with a would-be corpse-robber is curiously choreographed, with the acrobatics left to his opponent, and a thrown knife allowing the camera to cut away from part of the action. This is not the next generation’s martial-arts cinematography of the likes of Sonny Chiba – despite his undeniable charisma, Ichikawa lacked the ability to be a martial artist onscreen.

He was fortunate that the production of Shinobi no Mono concentrated not on the physicality of martial arts, but on a panoply of gadgets and ruses, establishing many of the tropes that would become commonplace in modern-day ninja movies. It was, for example, the first onscreen appearance of the now-ubiquitous shuriken or throwing star. The fight choreographers on the film were the martial artist Toshitsugu Takamatsu and his pupil Masaaki Hatsumi, who gleefully embraced a production that called for tricks and traps. In later life, Hatsumi would claim that Takamatsu had been the “last of the true ninja,” and that before he died, he had passed on all his training secrets. Hatsumi also served as an adviser on the James Bond film You Only Live Twice (1967), a scene in which an assassin drips poison down a thread in imitation of Goemon’s use of the “Tranquil Cessation” attack.

Tomisaburo Wakayama is suitably dastardly as Nobunaga, particularly in a scene in which he tortures a ninja captive, taking over when his own samurai lieutenants lack the will to cut off a man’s ears. In a harbinger of the danger Japan is in, Nobunaga’s son Nobuo (Katsuhiko Kobayashi) is ready to step in with evident enthusiasm. These bloodthirsty tyrants must be stopped… but who save Japan when the samurai are hell-bent on destroying each other?

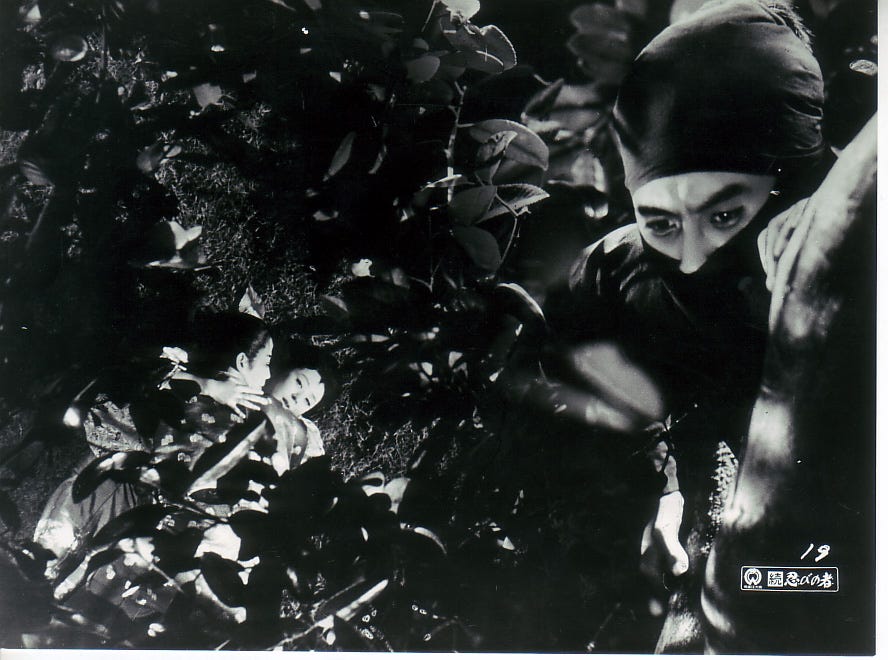

Where samurai films traditionally favour vast set-pieces on the battlefield, Shinobi no Mono relies on sneaking and stealth. In an era that is still curious about the minutiae of a ninja’s life, rather than focussing entirely on their stunts and tricks, a prolonged sequence observes the Master Mamochi Sandayu as he sets out on a mission, donning his split-toed tabi socks, sneaking out through a secret passage, and throwing off his apparent old age in an increasingly nimble journey, helped just a little by some gentle under-cranking of the camera. It helps, too, that this film made in the dying days of monochrome cinema was better able to shoot day-for-night than many later colour movies. For a black and white film, it is often very black, the contrast turned right down to accentuate the ninja’s rightful home in the shadows, the camerawork luxuriating in the bright sparks of thrown tapers, or the flash of moonlight on droplets of poison.

Inevitably, there is a large-scale battle scene, but this is where the ninja withdraw, laying down their calthrops and hurling their shuriken, and leaving the real-world actors to play out history as it happens. The influence of the ninja is obscured beneath the smoke of the battlefield and Goemon returns, safe for the moment, to his lover Maki (Shiho Fujimura). Actor Raizo Ichikawa, however, would never get to enact his revenge on the kabuki world by returning to the stage in triumph. He would succumb to cancer in 1969, aged 37.

As for the character of Goemon, the third Shinobi no Mono film, Resurrection (1963, Shin Shinobi no Mono), offered him the prospect of an escape from his gruesome historical fate. But that is another story.

Jonathan Clements is the author of A Brief History of the Martial Arts and Christ’s Samurai: The True Story of the Shimabara Rebellion.

OUR LATEST BUNDLE - AUGUST 2025

Our August bundle discount will automatically apply when 4 or more eligible titles are added to your cart, taking 10% off the total price.

Our August bundle (including Shinobi vol. 2, Through and Through, Senso and The Inquisitor + Deadly Circuit) ends June 4th.

Another fascinating essay!